Death of Osip Mandelstam (December 27, 1938)

Osip Mandelstam, one of the foremost Russian poets of the early twentieth century, was also celebrated for his memoirs and his cycle of poems dedicated to Armenia after his trip in 1930.

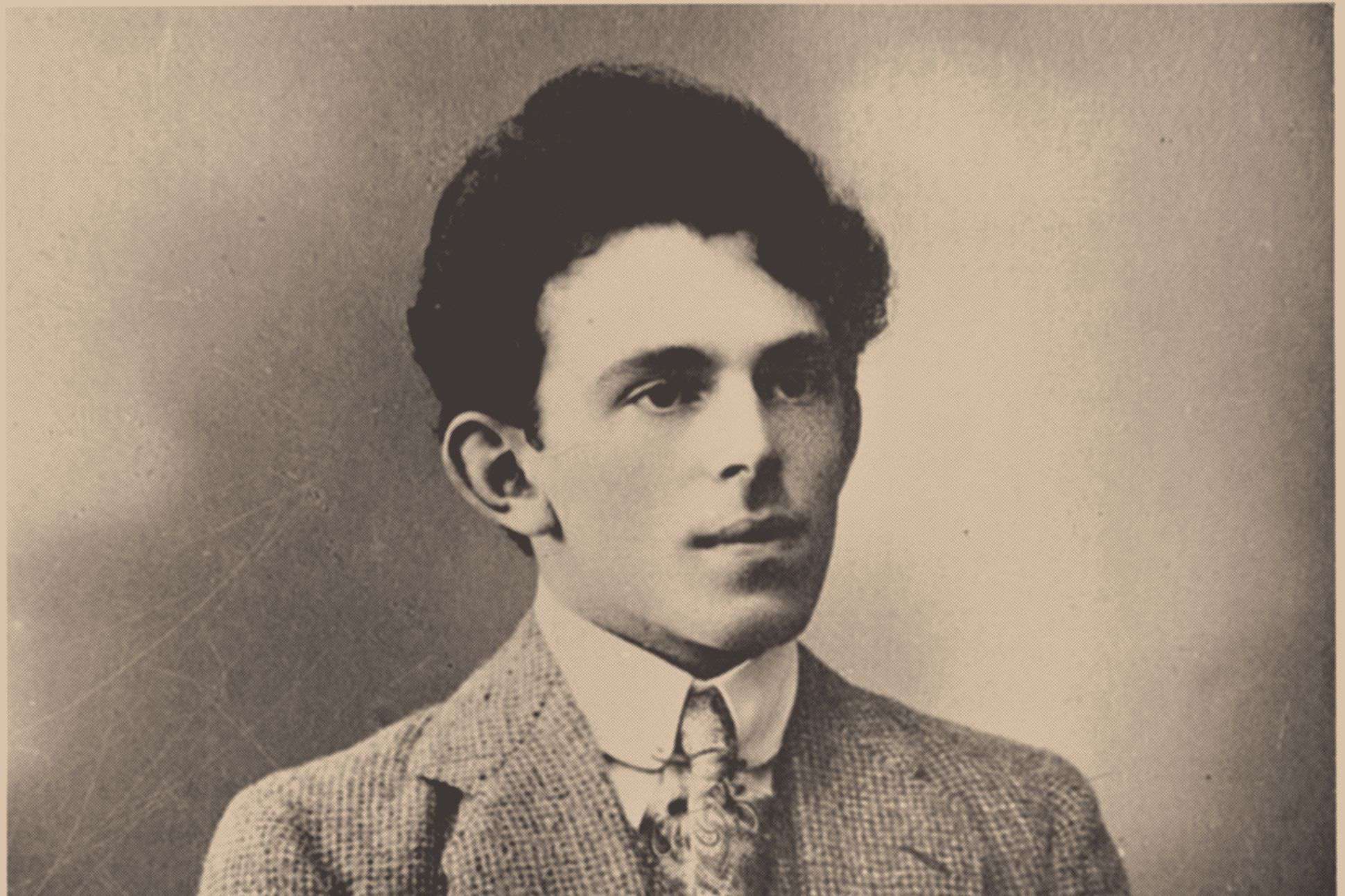

Mandelstam was born on January 14, 1891, in Warsaw to a wealthy Polish-Jewish family. His father was able to purchase the right to move his family to Saint Petersburg, where only a handful of Jews were allowed to live. In 1900, Mandelstam entered the prestigious Tenishev School. His first poems were published in 1907 in the school’s almanac.

In 1909, Mandelstam left St. Petersburg to attend the University of Heidelberg (Germany) until 1911, when he decided to continue his education at the University of St. Petersburg, from which Jews were excluded. He converted to Methodism and entered the university the same year but did not complete a formal degree.

Mandelstam’s poetry became closely associated with symbolist imagery. In 1911, he and several other young Russian poets formed the “Poets’ Guild.” The core of this group became known as the Acmeists. In 1913, Mandelstam wrote the manifesto for the new movement, The Morning of Acmeism, published in 1919. In 1913, he published his first collection of poems, The Stone, which was reissued in 1916 under the same title with additional poems included.

In 1922, he married Nadezhda Mandelstam (1899-1980) in Kiev, Ukraine, but the couple settled in Moscow. That same year, his second book of poems, Tristia, was published in Berlin. He almost completely abandoned poetry, concentrating on essays, literary criticism, memoirs (The Noise of Time and Feodosiya, both in 1925), and small-format prose (The Egyptian Stamp, 1928). He translated literature into Russian (19 books in 6 years) and then worked as a correspondent for a newspaper.

In 1930, Mandelstam traveled to Armenia. The Stalin regime was then sending writers to freshly annexed parts of the country. Mandelstam genuinely admired the land and saw in its proud, strong people a glimmer of hope for international socialism: “The Armenians’ fullness of life, their rough tenderness, their noble inclination for hard work, their inexplicable aversion to any kind of metaphysics, and their splendid intimacy with the world of real things—all this said to me: you’re awake, don’t be afraid of your own time, don’t be sly.”

At the end of 1930, on the long journey back to Moscow, Mandelstam composed a short cycle of poems about the country he had just left: “Not ruins, no, but a cutting-down of a mighty circular wood / Anchor-like stubs of cut oak-trees of a wild and legendary Christianity.” Traveling through Armenia was for Mandelstam a way of slicing cleanly through history, revealing the Greek, Roman, Hebraic, and Christian layers that together made Western civilization. The Armenian language, he wrote, was the noblest and most resilient kind of work, the heartiest, the most durable:

“The Armenian language cannot be worn out; its boots are stone. Well, certainly, the thick-walled word, the layers of air in the semivowels. But is that all there is to its charm? No! Where does its traction come from? How to explain it? Make sense of it?

I felt the joy of pronouncing sounds forbidden to Russian lips, secret sounds, outcast, and perhaps on some deep level, shameful.”

In the autumn of 1933, Mandelstam composed an epigram about Stalin, which he recited at a few small private gatherings in Moscow. The poem deliberately insulted the Soviet leader: “His thick fingers are fatty like worms,/ but his words are true as pound weights, / his cockroach whiskers laugh, / and the tops of his boots shine.”

Six months later, on the night of May 16–17, 1934, Mandelstam was arrested by three NKVD officers who arrived at his flat with a search warrant. He anticipated that insulting Stalin would carry the death penalty, but Nadezhda and Anna Akhmatova, her lifelong friend, started a campaign to save him and succeeded in creating a kind of special atmosphere, which helped give Mandelstam a reprieve. On May 26, 1934, Mandelstam was sentenced to three years’ exile in Cherdyn in the Northern Ural, where he was accompanied by his wife. When they arrived, he attempted suicide by throwing himself out of a hospital window. In June, Mandelstam was banned from the twelve largest Soviet cities but otherwise allowed to choose his place of exile. Osip and Nadezhda Mandelstam chose Voronezh. During these three years, Mandelstam wrote a collection of poems known as the Voronezh Notebooks.

Mandelstam’s three-year exile ended in May 1937, during the Stalinist purges. He was arrested again in May 1938 and charged with “counter-revolutionary activities.”

In August, Mandelstam was sentenced to five years in correction camps. He arrived at the Vtoraya Rechka (“Second River”) transit camp near Vladivostok in Russia’s Far East. On December 27, 1938, Mandelstam died of typhoid fever. His body, along with others, was buried in a mass grave in spring.

Nadezhda wrote memoirs about her life and times with her husband in Hope Against Hope (1970), where she also discussed their trip to Armenia, and Hope Abandoned. She also managed to preserve a significant part of Mandelstam’s unpublished work. Given the real danger that all copies of his poetry would be destroyed, she worked to memorize his entire corpus, as well as to hide and preserve select manuscripts, all while dodging her own arrest. In the 1960s and 1970s, as the political climate thawed, she arranged clandestine republication of Mandelstam’s poetry.