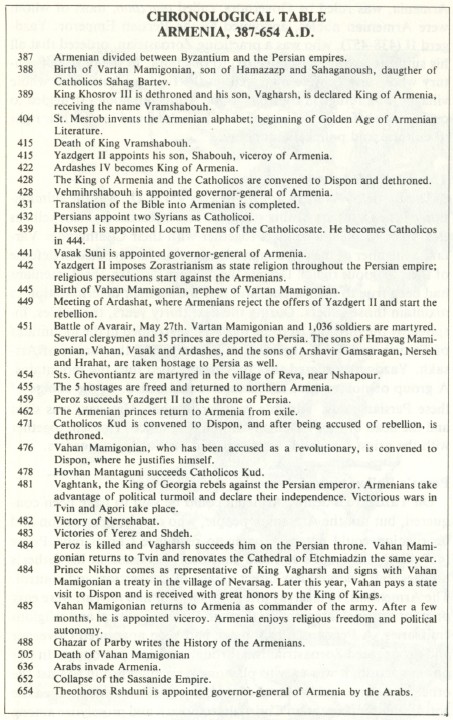

The Treaty of Nvarsag

T. J. Samuelian

THE TREATY OF NVARSAG

A DOCUMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS

484 – 1984 A.O.

In 301 A.O. the Armenians became the first nation to adopt Christianity as a state religion.

Caught between the Byzantine and Persian Empires, Armenia was partitioned in 387 A.O. by an agreement between Emperor Theodosius I of Byzantium and King Shapuh III of Persia. The larger portion fell under Persian rule.

In 484, after a half century’s struggle with their Persian overlords, the Armenians won certain religious and political liberties through a document which has come to be called the Armenian Magna Charla – The Treaty of Nvarsag.

This year marks the 1500th anniversary of the signing of that historic document. The Armenians, steadfast in their belief in human dignity, still strive to defend the concept of religious and cultural freedom embodied in that treaty signed sixty generations ago.

Armenia 400-450

Armenia was partitioned by Byzantium and Persia in 387 A.O. In the years immediately following the partition, the Armenian Arshaguni dynasty continued to rule, though subject to the Persian crown. In accordance with a 100-year treaty between Persia and Rome, the Armenian nobles were allowed to maintain military forces to defend the country; the Church was permitted to function; and the people were free to profess and practice Christianity, which had been adopted as the state religion only a few generations before. It was a period of great cultural development. Mesrop Mashdots created the Armenian alphabet. The Bible and Christian rites were translated into Armenian. National literature and history flourished in what has come to be known as the golden age of Armenian literature.

Religious Persecution under Yazdgerd II

This period of toleration and progress came to an end with the death of the Armenian king Ardashes IV in 428 and ascension of Yazdgerd II to the Persian throne ten years later. Thereafter, Armenia, was ruled by Governors, called marzpan, most of whom were Armenian nobles, appointed by the Persian Emperor. Yazdhis subjects likewise be converted to this faith. In the next half century whole armies were martyred on the fields of battle and whole villages took refuge in the hills, as the Armenian nobles struggled to organize an effective defense of their homeland and secure their right to cultural and political autonomy.

The Battle of Avarayr

The Battle of Avarayr, fought in May 451 A.O., was the culmina tion of the first part of this struggle. The historian Eghishe tells us that 1036 Armenian soldiers together with their Commander Var tan, a member of the prominent Mamigonian family, died in defense of their religious rights. Despite the military disaster, the Armenians had been true to their beliefs and had shown their determination to maintain those beliefs. During the next thirty years, the nobles, in spired by the memory of those martyrs, regrouped in the mountains of Tmorik and Tayk, the wilds of Khaldik, and the forests of Artsakh. Yazdgerd ordered that they be pursued into the mountains. A group of nobles were taken captive and exiled. In the course of these Persian raids, Vartan’s younger brother, Hmayag, was slain and the head of the Armenian Church, Catholicos Hovsep, together with the priest Ghevond, were executed on Yazdgerd’s orders.

Peroz’s Policy toward Armenia

On Yazdgerd’s death, Armenia could be said to have been conquered, but not the Armenian people, who despite persecution and deprivation could not be brought to renounce Christianity. Peroz (457-484), Yazdgerd’s son and successor, persisted in his father’s policies, but adopted less direct means of conversion and control. The Armenians, in disarray after years of war and retreat, were easy prey for external intervention through Persian political and religious emissaries. A Persian, Adrvshnasp, had been appointed Governor and propagated Zoroastrianism through political patronage. In this power vacuum it was easy to play one Armenian group against the other in order to gain control of the country. Peroz encouraged the anti-Byzantine, Nestorian Christians to preach and proselytize among the Armenians and thereby undermine the Armenian Apostolic Church. The Catholicos Kiwd, who perceived the danger of this divisiveness, appealed to Byzantium, but it was to no avail. The Romans and Byzantines were themselves beseiged by the Huns and Goths and could neither spare the military or financial means to assist the Armenians nor risk antagonizing the Persians and becoming engaged in combat on a second front.

Armenian Unrest Grows

In the meantime, the 25 Armenian nobles who had been taken captive after the battle of Avarayr, were set free and returned to their homeland after serving in campaigns against the Kushans on Persia’s eastern frontier. Within Armenia, Vahan, the son of Hmayag and nephew of Vartan Mamigonian, rose to the head of this noble family. In a land deprived of secular and religious leaders for over a generation, a new leadership was beginning to emerge. As part of his diplomacy, Peroz appointed Vahan tax-collector. Vahan carried out his duties with a show of loyalty and Peroz cleared his family’s name of past rebellion.

Tension between the Armenians and Persians were growing however. The Persian Governor was gradually divesting the Arme nian Christian nobles of their estates and enriching his collaborators. Irritated that Vahan enjoyed the good favor of the crown, the Gover nor began plotting against Vahan and gave Vahan yet more cause to resent Persian rule. In addition to religious and cultural repression, the nobility and peasantry were being driven to poverty by Persian rule. The burden of supporting the Persian army stationed in Armenia drained the countryside of its wealth and brought tremendous hardship on the people.

At this point, Armenian nobles were again serving in the Persian army which was engaged in combat in two neighboring countries. The Georgian king, Vakhtang, had declared war on the Persians in response to a plot by a Georgian nobleman, Vazken, who had converted to Zorastrianism and abandoned his wife, Shushanig, Vartan Mamigonian’s daughter, for a member of the Persian household. In the north-eastern part of the Persian Empire, the Hephthalites had begun to rebel and Peroz was obliged to dispatch troops to maintain control of that frontier as well.

The Armenian Resistance under Vahan Mamigonian

Vaghtang called for the Armenians to join the rebellion, promising support from the Georgians and the Huns. The Armenians had reason enough to rebel. Conditions within the country were in tolerable; Armenian and Christian sensibilities had been offended by Peroz’s unscrupulous representatives and collaborators; the memory of independence was still alive and the desire to reestablish it growing stronger. With the Persians already engaged on two fronts, the international situation seemed to favor a quick settlement of Armenian grievances. Nevertheless, Vahan Mamigonian was wary of the Georgian king’s promise of support, for the Armenians had been disappointed so many times by allies in the past. The nobles, gathered around Vahan, protested that they were determined to recover their rights with or without help from Vaghtang or Byzantium, and so they decided to take up arms against the Persians in the fall of 481. An Armenian government was established with Sahag Pakraduni at its head. The rebels, under Vahan’s command, launched an attack on the Persian occupation forces almost immediateiy. The Persian governor, who was forewarned of the at tack, took refuge in the fort at Ani.

During the following four years, the army recorded victory after victory under Vahan Mamigonian’s generalship. In the course of these battles, the governor Sahag Pakraduni, and Vahan’s brother lost their lives. So did the former Persian governor, Adrvshnasp. The first major battle took place at Agori in the fall of 481. The heads of the Armenian forces – Vasag Mamigonian, Papken Siwni, the brothers Nerseh and Hrahad Gamsaragan, and the brothers Adorn and Arasdam Knuni – led their troops with such bravery that the 300 Armenians emerged victorious against the 7000-man Persian force. In the north the Georgian king Vaghtang was not so successful. Vahan responded to his call for assistance and thus found himself entangled in military action on the northern border of Armenia near the Kur River. At just this moment, the Persians suffered a devastating defeat against the Hephthalites, during which Peroz lost his life.

The Treaty of Nvarsag

King Vagharsh (484-489), Peroz’s brother and successor, wishing to extricate himself from the hostilities, sent Nikhor Vshnasptad to open negotiations with the Armenians. Vahan, who from the first had been reluctant to pursue the Armenian cause through military defiance of his overlord, took up the offer of peace on the following three conditions:

- Armenians are to be free to practice Christianity; all efforts to convert the Armenians to Zoroastrianism are to cease, and all Zoroastrian priests and altars are to be removed from Armenia.

- State offices are to be filled and discharged justly, and the nobles are to be restored to their positions of local authority.

- Armenian grievances are to be heard and resolved by the King directly, so as to avoid the corruption and false witness which had stung Vahan’s honor so deeply.

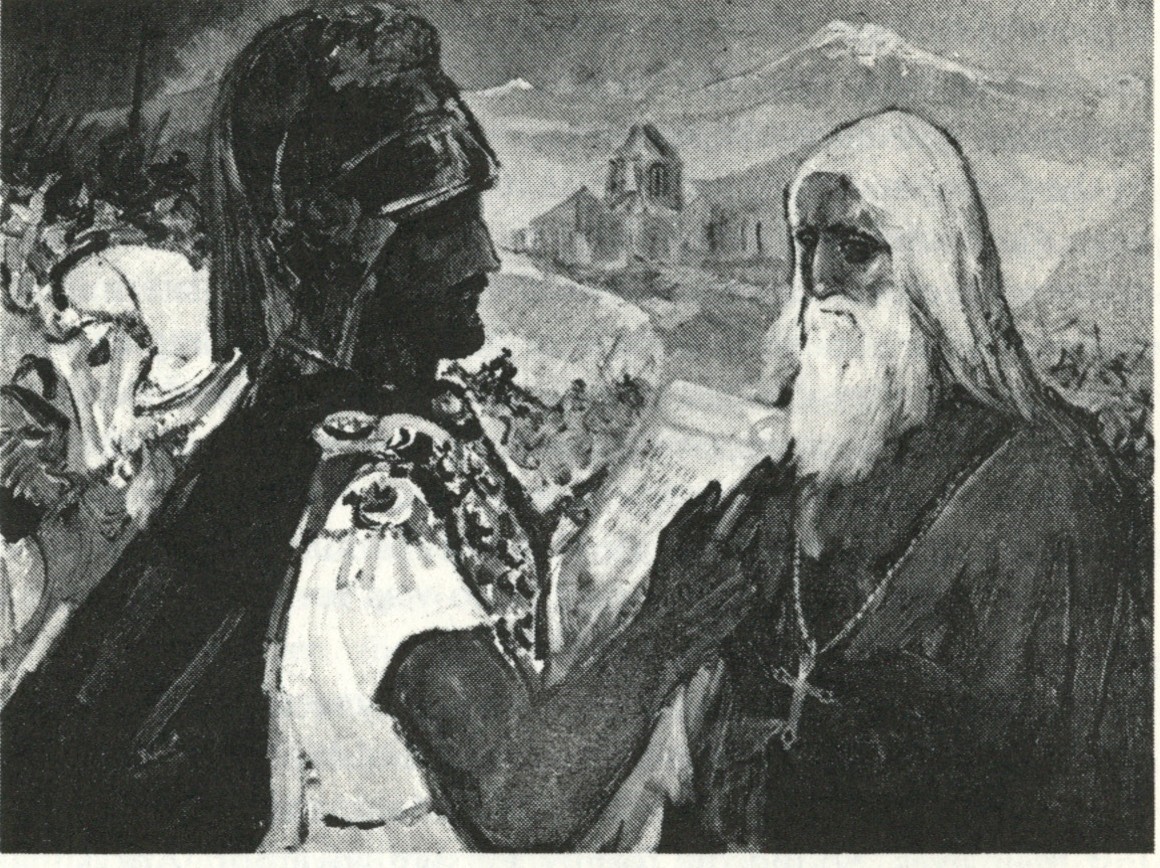

THE TREATY OF NVARSAG

Original painting by Paul Giragosian

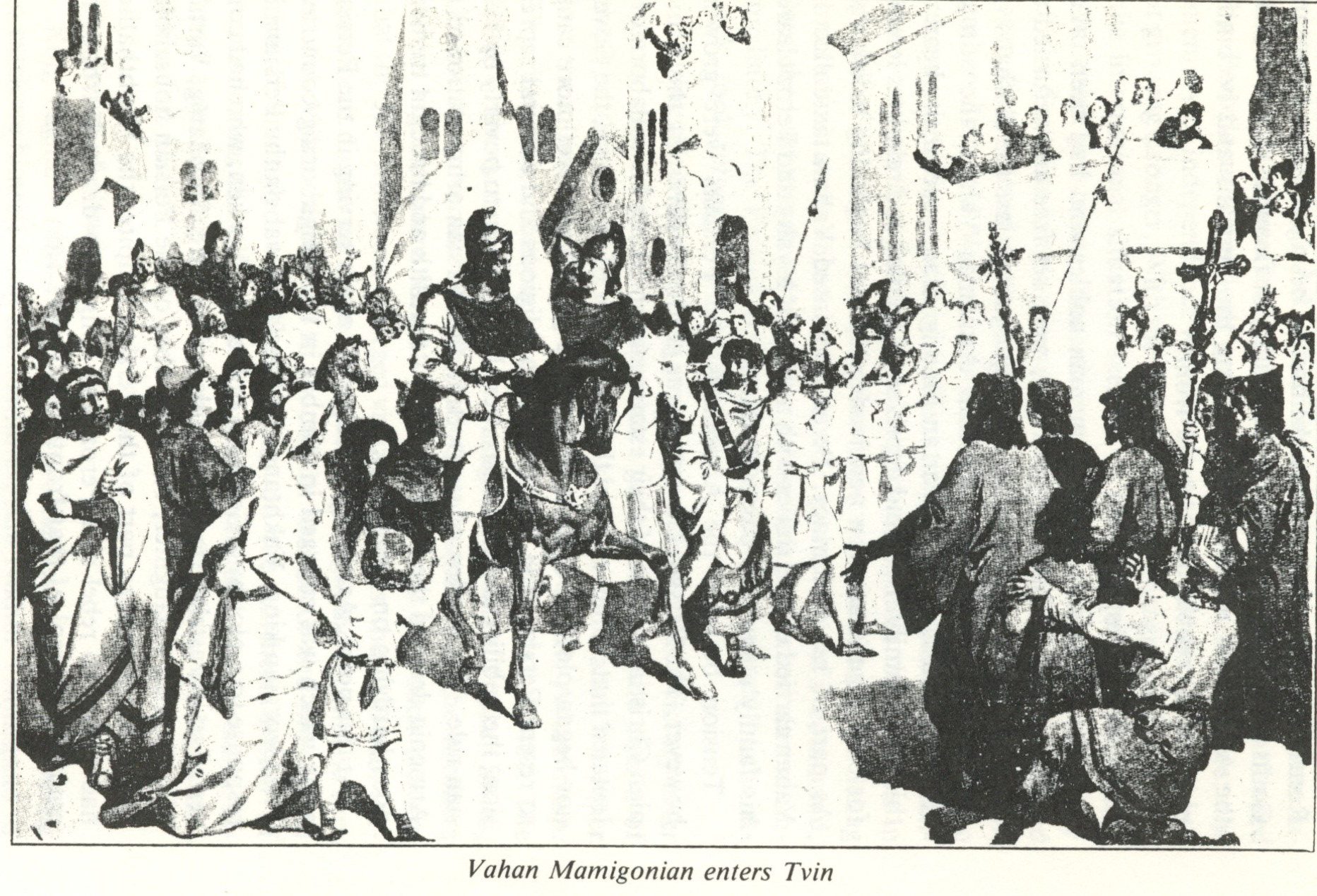

These proposals were accepted by the King’s representative, who was encamped at Nvarsag; hence the agreement came to be known as the Treaty of Nvarsag. Vahan concluded the treaty in person and amnesty was granted to him and the other rebels. Shortly thereafter Vagharsh elevated Vahan to the position of Governor General. Majestic ceremonies were held at the Cathedral of Dvin with the blessing of Catholicos Hovnan Mandakuni. During his twenty-year rule, Armenia prospered in peace founded on dignity, toleration and freedom.

Over seven hundred years before the Magna Charta (1215), the Treaty of Nvarsag established, by mutual consent, a Jaw to regulate the relations between king and noblemen. After years of struggle, the Persian King Vagharsh concluded that it was better to rule by Jaw and toleration than by force a.d persecution. In return, the Armenian nobles pledged their loyalty contingent on the just execution the treaty. Against great odds the small Armenian force under Vahan’s command had, through their sacrifice and commitment, secured peace with cultural and religious freedom.

It is their ideals and commitment, along with the values of toleration and the rule of just laws, that we still celebrate and commemorate today after 1500 years.